Rivals defeat TCPA claims on home turf as Yahoo! takes big loss in the Third Circuit

In a series of cases following the FCC’s new omnibus TCPA ruling—which held that everything from smartphones to e-mail servers are now autodialers—the judges of the Northern District of California have done their best to keep the TCPA’s grimy little paws off of emerging tech companies. Home town favorites such as AOL, Whispertext and Groupme have all received some much-needed love in recent TCPA decisions. (Of course, so has Sapphire Gentlemen’s Club, but I won’t go there….) See Derby v. AOL, Inc., Case no. 15-cv-00452 RMW (N.D. Cal. Sept. 11, 2015); McKenna v. Whisptertext, Case no. 14-cv-00424—PSG (N.D. Cal. Sept. 9, 2015) Luna v. Shac, LLC, dba Sapphire Gentlemen’s Club, Case no. 14-cv-00607-HRL (N.D. Cal. Aug. 19, 2015); and Glauser v. GroupMe, Inc., Case no. 11-2584 PJH (N.D. Cal. Feb 4, 2015).

Each of these decisions finds that seemingly automated systems operate with sufficient “human intervention” to remove the equipment from the FCC’s expansive new definition of ATDS. A quick gander at these cases, however, leaves one wondering whether “human intervention” might reside in the eye of an eager beholder:

For instance in Derby v. AOL, Inc., Case no. 15-cv-00452 RMW (N.D. Cal. Sept. 11, 2015) the court found that AOL’s instant messenger platform is not an ATDS because text messages are not sent by the program unless: i) an AIM user composes an individual message; ii) an AIM user changes his status (which then generates an automatic update message to users); or iii) a user logs off (triggering an “auto-reply” response to users). Id. at *4. The case seems to stand for the proposition that text messages automatically generated by a messaging platform as the result of user-programmed preferences do not qualify under the TCPA, even if the conduct triggering the text message is not otherwise communicative in nature (such as logging off of a messenger program).

In McKenna v. Whisptertext, Case no. 14-cv-00424—PSG (N.D. Cal. Sept. 9, 2015) the court held that allegations a social messenger app sent text invitations “only at the user’s affirmative direction” foreclosed any possibility that an ATDS was utilized. Id. at *6. This is true although the Complaint alleged the app used an “automated process to harvest phone numbers from [the app] user’s phone and upload them to a third-party platform” which then “uses [an] automated process to send invitational messages to those numbers…” Id. at *7.

In Luna v. Shac, LLC, dba Sapphire Gentlemen’s Club, Case no. 14-cv-00607-HRL (N.D. Cal. Aug. 19, 2015) the court granted a Defendant summary judgment finding that sufficient human intervention was demonstrated where: i) numbers were selected and transferred into a third-party database; ii) the content of messages were drafted by a human being; iii) the timing of the messages was selected by the sender; and iv) a user had to hit “send” to transmit the messages. Id. at *4. This is so although the messaging platform then sent the sender’s marketing material on an automated basis to the list of numbers selected by the sender.

Finally, in Glauser v. GroupMe, Inc., Case no. 11-2584 PJH (N.D. Cal. Feb 4, 2015) the court granted summary judgment to the Defendant where an app user created a “group” of cell numbers to receive texts from other group members. Although a subsequent welcome message was then automatically sent to all recipients—without the group creator’s knowledge or request—the court found that the process of selecting numbers to create the group-text membership constituted sufficient “human intervention” to remove the system from the TCPA’s ATDS definition. Id. at *6.

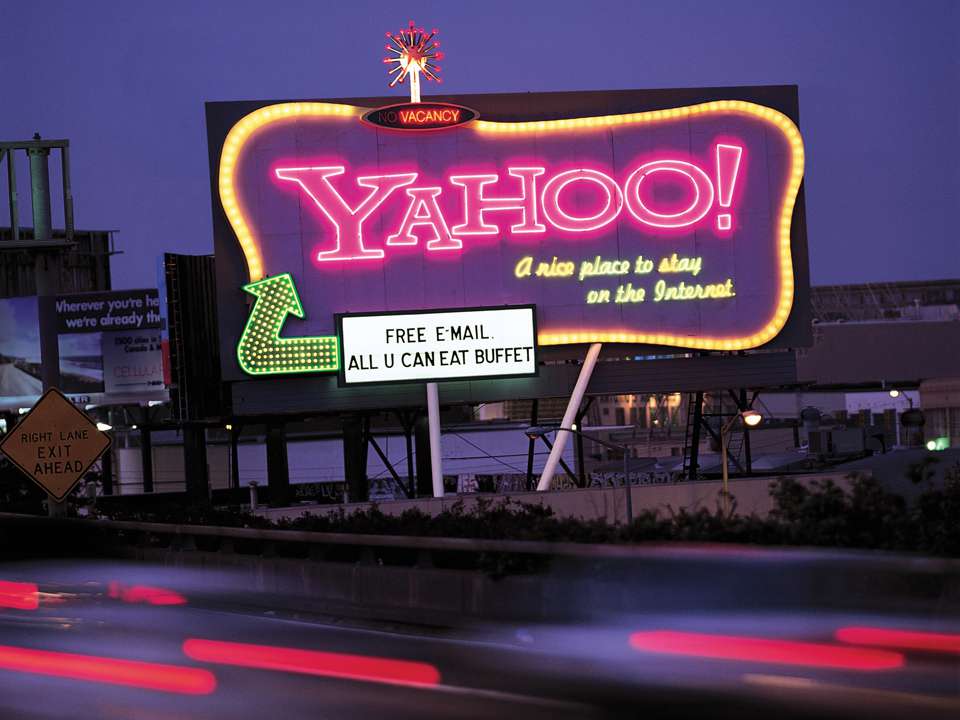

By stark contrast, however, the Third Circuit just roughed-up Yahoo! on the same issue in a decision that could end up costing the company over $13MM in that case alone. See Dominguez v. Yahoo, Inc., 2015 WL 6405811, at *2-3 (3rd Cir. 2015). The court found that Yahoo!’s messenger system could be an ATDS if it has even “the latent ‘capacity’ to place calls to randomly or sequentially generated numbers” and apparently without regard to whether human intervention was used to send the specific messages at issue. The Third Circuit remanded for further proceedings but, importantly, reversed the District Court’s summary judgment in favor of Yahoo!. Notably, Yahoo!’s system appears to operate identically to the AOL messenger program that the venerable Judge Whyte threw out of court—at the pleadings stage—in the Derby case.

That leaves one to wonder, could it be that Silicon Valley judges are willingly straining their eyes to find “human intervention” lurking within automated systems merely to protect their favored tech titans?

Fun though it is to imagine some imminently-transparent conspiracy emerging in the world’s highest-tech courthouses, the short answer is “no.” Silicon Valley judges are both tech-savvy and pragmatic enough to know that social messaging platforms are simply not within the intended scope of the TCPA. These systems operate by sending unique, one-at-a-time, messages between users, and (for the most part) do not produce the sort of blast-disseminated telemarketing materials the TCPA sought to prohibit. Automated responses prompted by user settings—such as auto-replies and log-off notifications—all depend on user-specific actions that the messaging platform merely makes available to users but does not, itself, initiate. From this perspective, therefore, the “human intervention” decisions the Northern District is churning out appear well-reasoned, thoughtful and—dare I say—correctly decided.

While the FCC may feel that these courts are running roughshod over its newly-inked order—and they kind of are—it knowingly elected not to address the definition of “human intervention” in its Omnibus ruling. See 2015 TCPA Omnibus Ruling par. 17. (“How the human intervention element applies to a particular piece of equipment is specific to each individual piece of equipment, based on how the equipment functions and depends on human intervention, and is therefore a case-by-case determination.”) As such it left dangling the very thread by which courts are now so easily unraveling the application of its new autodialer definition.

The Commission ought not be surprised that on a clear judicial day human intervention might be spotted even on a distant horizon, across miles and miles of otherwise automated landscape. And in Silicon Valley, where judges deal with emerging technology daily, the forecast undoubtedly calls for more bright and sunny judicial days ahead.

The judicial weather report in the Third Circuit does not appear so temperate, however. Looks more like a foggy winter in Sunnyvale…