The US Sentencing Commission Votes for Fundamental Fixes to the Sentencing Guidelines

By Alan Ellis and Mark H. Allenbaugh

On April 9, 2015, the US Sentencing Commission voted to fundamentally fix some portions of the US Sentencing Guidelines that have been in need of addressing for quite some time. On April 30, 2015, the Commission submitted to Congress amendments to the federal sentencing guidelines pursuant to its authority under 28 U.S.C. §994(p). These amendments will go into effect on November 1, 2015, barring congressional action.

As several of the Commissioners observed during the April 9th hearing, the Commission’s votes constitute a modest but important reversal of the brute-force approach driven by “loss” used to measure the harm caused by the offense conduct and a return to more refined measurements of a defendant’s actual culpability. For many defendants, this will have the effect of lowering the advisory sentencing guidelines range.

This article reviews some of the changes, which in most cases reflect a welcomed emphasis on a defendant’s actual culpability.

Jointly Undertaken Criminal Activity

Conspiracy cases often involve complex questions of fact regarding the liability of one conspirator for another. For purposes of trial, conspirator A can be held liable for the overt acts of conspirator B even if A had no actual knowledge of B’s acts, as long as B’s acts were in furtherance of the conspiracy. But the same does not necessarily hold for purposes of sentencing, and this has led to considerable confusion in the courts.

At the trial level, courts are concerned with liability, while at sentencing the issue turns to culpability. Or as the Commission long has noted, “[t]he principles and limits of sentencing accountability…are not always the same as the principles and limits of criminal liability.” This has nevertheless led to considerable confusion inasmuch as courts often equate trial liability with sentencing accountability. For example, in a fraud conspiracy involving A and B that resulted in $15 million in investor losses, while A and B may criminally liable for the conspiracy, the guidelines recognize that A may not be as accountable—in other words, less culpable—as B especially where A’s role was comparatively small. The same, of course, holds true for drug conspiracies.

The Commission now has clarified conspirator A can only be held accountable for the acts of conspirator B where (1) B’s acts were within the scope of criminal activity that A agreed to jointly undertake, (2) B’s acts were in furtherance of that criminal activity and (3) B’s acts were reasonably foreseeable in connection with that criminal activity. The first criterion, which now has been added to the guidelines, clarifies that within conspiracies, each co-conspirator should only be held accountable for conduct that he actually agreed to jointly undertake with the other conspirators.

This clarification hopefully will reverse the trend of automatically holding one conspirator accountable for the conduct of all other conspirators regardless of the conspirator’s actual role in the offense. After all, holding a conspirator accountable only for the foreseeable conduct he agreed to undertake, which was in furtherance of the conspiracy, is a far better and fairer measure of a defendant’s culpability than otherwise.

Mitigating Role

With respect to measuring culpability, section 3B1.2 of the guidelines provides for a downward adjustment of between two and four levels where an offender is found to be a minor or minimal participant in a conspiracy. The question has been whether that determination turns only on the conduct of co-conspirators in the case at hand, or whether a court is also to look at other cases involving those who have committed similar crimes.

The Commission has now voted that courts are only to look at the relative culpability of co-conspirators in the case before them, rather than engage in a review of similarly situated defendants in other cases. This move likely will reduce unnecessary litigation on the issue and hopefully increase application of this downward adjustment, which currently is only awarded an abysmally 6.9% of the time.

Economic Offenses

Finally, the Commission issued several amendments to USSG §2B1.1 that affect sentencing for economic offenses. These amendments continue the Commission’s emphasis on fine-tuning the measurement of an offender’s culpability and counter some historically over-simplistic measurements of offense harm.

1. Inflationary Adjustment

The Commission voted to revise economic tables to account for inflation. For example, the fraud-loss table at USSG §2B1.1(b)(1) and tax loss table at USSG §2T4.1 now have had their respective limits increased, which can serve to mitigate punishment. Under the current iteration of the guidelines, a loss amount of $500,000 will result in an offense level increase of +14. However, come November 1, 2015, the same loss amount will only result in an increase of +12. Below is the final table for USSG §2B1.1(b)(1).

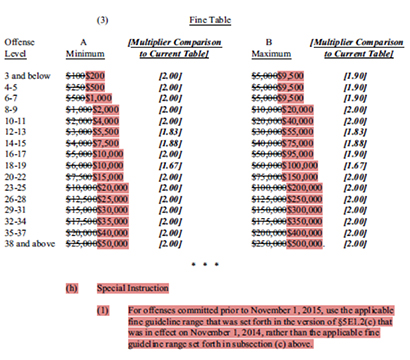

But what the Commission giveth, it also taketh away. In addition to adjusting the loss tables for inflation, which has a mitigating effect, the fine tables also have been adjusted, which has a significant punitive effect. Indeed, the fine ranges now are approximately doubled. Practitioners, therefore, should be aware of this new, onerous modification, and note the built-in ex post facto limitation stated within the table itself. The revised fine table for individuals with the “special instruction” is below:

2. Intended Loss

For economic crimes, the guidelines look primarily to the amount of “loss” to determine offense seriousness. For example, in a typical Ponzi scheme, loss generally is equivalent to the total amount of money all investors lost, i.e., “actual loss.” However, loss also can include so-called “intended loss.” Returning to the Ponzi scheme example, intended loss thus would be equivalent to the money the offender intended investors to lose, e.g., where the offender was arrested before he could cash an investor;s check. If the intended loss is greater than the actual loss, then the guidelines direct a sentencing judge to use the amount of intended loss.

The concern has been how to measure intended loss. Is it a subjective or objective measure? Consistent with its focus on the actual culpability of the offender reviewed in the sections above, the Commission now has clarified that intended loss is to be measured by the defendant’s subjective intent.

3. Victims Table

Here, the Commission has expanded the enhancement by adding an either/or element of “substantial financial hardship.” While the government must now prove in certain cases that victims of the offense suffered substantial financial hardship, this alone can lead to an enhancement in some cases, even if the number of victims is below the threshold, for example, if the offense involved less than ten victims. Currently, there is no such enhancement. Under the proposed amendment, if the offense involved less than ten victims but resulted in substantial financial hardship to one or more, there is a two level increase.

A four-level enhancement is mandated where the offense resulted in substantial hardship to five or more victims. If the offense resulted in substantial hardship to 25 or more victims, the increase is six levels. The revised victim table is below:

4. Sophisticated Means

Here again the Commission has revised the guidelines to focus on the defendant’s culpability, as opposed to the nature of the offense. Where the “sophisticated means” enhancement at USSG §2B1.1(b)(10)(C) traditionally has looked to the nature of the offense itself in terms of sophisticated, the guidelines will now direct courts to determine whether “the defendant intentionally engaged in or caused the conduct constituting sophisticated means.” This amendment hopefully will have the effect of reducing what oftentimes is the automatic application of the enhancement based solely on the nature of the offense itself, regardless of the defendant’s intent.

5. Fraud on the Market

In 2012, Commission adopted a controversial “modified rescissory method” (“MRM”) for determining loss in securities fraud cases, and indicated that there was a “rebuttable presumption” that this method should be used by courts in such cases. To say the least, it did not meet with a receptive audience and in fact proved quite unwieldy and inaccurate. Accordingly, the Commission wisely voted to remove the rebuttable presumption in favor of that method and stated that courts now may use “any method that is appropriate and practicable under the circumstances.”

Still, the Commission left in the modified rescissory method identifying it as but one method “the court may consider” when calculating loss in securities fraud cases. This prompted Commission Vice-Chair Judge Charles Breyer to object during the hearing that the method was not completely stricken from the guidelines. Judge Breyer rightly indicated that there is no evidence courts can use MRM effectively and instead should use the civil standard for determining losses in securities fraud class actions unanimously adopted by the US Supreme Court in Dura Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Broudo.

In all events, that the Commission corrected this unwise presumption in favor of an otherwise unworkable method was quite welcome and will avoid needless litigation over the propriety of MRM in future cases.

Conclusion

As reviewed above, the Commission’s proposed changes to the guidelines reflect an emphasis on actual culpability and a move away from brute and unrefined measures of offense seriousness that all too often result in unreasonably long sentences. As Judge Pryor—one of the voting Commissioners—also recognized, the guidelines in its current form were drafted under a mandatory era, and therefore are “unsustainable” in a now-advisory system. The Commission’s amendments, while modest, nevertheless address some fundamental flaws in the sentencing guidelines, which the Commission emphasized it will continue to evaluate and calibrate to ensure that federal sentencing is not only just and fair, but effective.

The United States, with only 5% of the world’s population, incarcerates 25% of the world’s prisoners. That the oldest democracy in the world continues to incarcerate more of its citizens per capita and in greater number than any other nation on earth—and in which the federal government incarcerates more individuals than any single state—is a sad and shocking statistic. With the federal Bureau of Prisons housing inmates at over 30% of its rated capacity, we simply cannot afford to continue our fixation on incarceration, especially for low level non-violent, first-time offenders. The Commission’s modest changes nevertheless constitute a major recognition of this problem and its commitment to smarter sentencing.

Alan Ellis and Mark H. Allenbaugh originally published this article, The US Sentencing Commission Votes for Fundamental Fixes to the Sentencing Guidelines, in JURIST – Hotline, May 9, 2015.