A Potential Route to RADV Judicial Review: Part II

In part I, we discussed whether federal district courts could exercise jurisdiction under the federal-question statute over legal challenges to overpayment determinations made by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under the agency’s controversial Risk Adjustment Data Validation (RADV) program for Medicare Advantage (MA) organizations. After concluding that existing Supreme Court precedent provided a substantial basis for arguing in favor of such jurisdiction, we left for another day the antecedent question whether MA organizations must exhaust administrative remedies before filing suit under the federal-question statute.

The seemingly straightforward exhaustion question presents a host of considerations that belie a one-size-fits-all answer. The practical answer likely depends on the nature of the specific overpayment determination at issue and the grounds upon which the MA organization wishes to challenge that determination.

RADV Administrative Remedies Generally

Before delving into the question whether one must exhaust administrative remedies, let us look briefly at the administrative remedies CMS has created for RADV overpayment determinations. Those administrative remedies, which are not required by statute, are found in a single regulation: 42 C.F.R. §422.311.

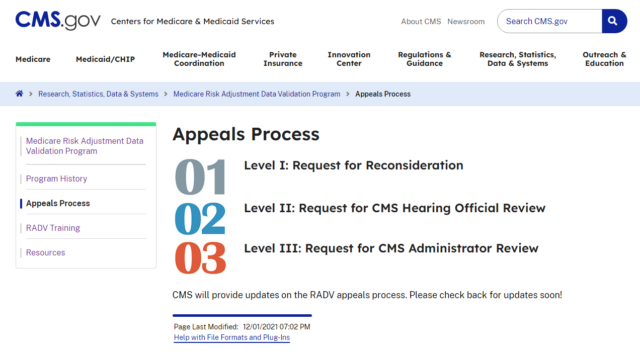

First promulgated in 2010 and amended on multiple occasions since then, §422.311 establishes a three-level appeals process through which MA organizations “may” appeal RADV audit results. As reflected by the image below taken from the CMS website in April 2023, the three levels of an administrative appeal are (1)reconsideration, (2)CMS hearing officer review, and (3)CMS Administrator review.

Importantly, however, the scope of what issues MA organizations may appeal administratively is expressly limited by that same regulation. For example, §422.311(c)(3) states that MA organizations “may not appeal the [Secretary of Health and Human Services’] medical record review determination methodology or RADV payment error calculation methodology.” (Emphasis added.) This express prohibition suggests that MA organizations will be unable to obtain any administrative review of such critical legal issues as whether CMS has the statutory authority to conduct contract-wide extrapolation, as well as challenges to the sampling and extrapolation methodologies used. Instead, administrative appeals appear most likely to focus on enrollee-specific documentation issues and/or mathematical errors, the former of which must be addressed before an administrative appeal may move forward on the latter. See §422.311(c)(5)(iii)(B).

Moreover, for MA organizations concerned with the length of time it might take to exhaust administrative remedies—recall that CMS has used language suggesting that when it makes an overpayment determination, the agency will offset the amount in question from the health plan’s next monthly capitation payment (and from subsequent monthly capitation payments, if necessary)—§422.311 does not impose time limits by which the first and second stages of an administrative appeal must be completed.

In other words, the regulation does not require that a reconsideration decision or CMS hearing officer decision be issued within a set period of time. See §422.311(c)(6), (7). And while not free from doubt, the language of §422.311 further suggests that CMS might believe that the Administrator has complete discretion regarding the amount of time she may take to acknowledge her discretionary decision to review the CMS hearing officer’s decision, which discretionary decision by the Administrator then triggers a right to submit additional briefing before the Administrator issues a ruling on the merits. See §422.311(c)(8)(iii), (iv)(A).

In short, the administrative remedies CMS has established in the RADV context appear to be both incomplete and prone to significant delay.

Section 405(g)-Based Exhaustion

Many, if not most, Medicare-related cases reach court only after the plaintiffs have presented their legal arguments to CMS and have exhausted their administrative remedies. The primary reason for that phenomenon is not patience on the part of the plaintiffs. Most such plaintiffs would prefer to be in court as quickly as possible. Instead, such delays often are required as a matter of law based on the interaction between three different subsections of 42 U.S.C. § 405: namely, subsections (b), (g), and (h).

Those subsections state, in relevant part:

(b) Administrative determination of entitlement to benefits; findings of fact; hearings....

(1) The Commissioner of Social Security is directed to make findings of fact, and decisions as to the rights of any individual applying for a payment under this subchapter. Any such decision by the Commissioner of Social Security which involves a determination of disability and which is in whole or in part unfavorable to such individual shall contain a statement of the case, in understandable language, setting forth a discussion of the evidence, and stating the Commissioner’s determination and the reason or reasons upon which it is based. Upon request by any such individual ... the Commissioner shall give such applicant ... reasonable notice and opportunity for a hearing with respect to such decision, and, if a hearing is held, shall, on the basis of evidence adduced at the hearing, affirm, modify, or reverse the Commissioner’s findings of fact and such decision....

…

(g) Judicial review

Any individual, after any final decision of the Commissioner of Social Security made after a hearing to which he was a party, irrespective of the amount in controversy, may obtain a review of such decision by a civil action commenced within sixty days after the mailing to him of notice of such decision .... Such action shall be brought in the district court of the United States for the judicial district in which the plaintiff resides, or has his principal place of business ....

(h) Finality of Commissioner’s decision

The findings and decision of the Commissioner of Social Security after a hearing shall be binding upon all individuals who were parties to such hearing. No findings of fact or decision of the Commissioner of Social Security shall be reviewed by any person, tribunal, or governmental agency except as herein provided. No action against the United States, the Commissioner of Social Security, or any officer or employee thereof shall be brought under section 1331 ... of title 28 [i.e., the federal-question statute] to recover on any claim arising under this subchapter [i.e., subchapter II, 42 U.S.C. §§401–434].

Readers of our previous installment will recall that despite its references to the “Commissioner of Social Security” and subchapter II, §405 is relevant to Medicare because the Medicare Act cross-references particular subsections of §405. See 42 U.S.C. §1395ii. Particularly astute readers, however, will recall that the first two subsections block-quoted above—subsections (b) and (g)—are not so cross-referenced by the Medicare Act. Instead, specific portions of the Medicare Act confined to particular categories of disputes expressly provide for a subsection (b) hearing and subsequent judicial review under subsection (g) by expressly cross-referencing those subsections as they appear in §405. See, e.g., 42 U.S.C. §§1395w-22(g)(5), 1395cc(h)(1)(A), 1395ff(b)(1)(A), 1395rr(g)(3).

Not so in the RADV context.

That fact may ultimately prove to MA organizations’ benefit. Why? Because the Supreme Court has interpreted §405(g)—which provides for judicial review “after any final decision of the [Secretary] made after a hearing”—as imposing two prerequisites to judicial review under §405(g). First, the legal claim must have been presented to the Secretary. This “presentment” requirement cannot be waived by the Secretary or by a reviewing court. Mathews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319, 328 (1976). Second, the claimant must have exhausted administrative remedies following the initial denial of its legal claim, although such exhaustion may be waived by a court over the objection of the Secretary under certain circumstances. See id. at 330.

In short, a substantial argument can be made that the two prerequisites to judicial review under §405(g) do not apply to RADV overpayment determinations because §405(g) does not govern judicial review of such determinations.

Exhaustion Otherwise Required?

Assuming for the sake of discussion that the presentment and exhaustion requirements of §405(g) do not apply in the RADV context, CMS may nonetheless argue that a MA organization must still exhaust its administrative remedies before filing suit under the federal-question statute.

In relevant part, the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) provides that “final agency action for which there is no other adequate remedy in a court [is] subject to judicial review.” 5 U.S.C. §704. Section 704 goes on to state: “Except as otherwise expressly required by statute, agency action otherwise final is final for the purposes of this section whether or not there has been presented or determined an application for a declaratory order, for any form of reconsideration, or, unless the agency otherwise requires by rule and provides that the action meanwhile is inoperative, for an appeal to superior agency authority.” Id. This latter provision, the Supreme Court has explained, “explicitly requires exhaustion of all intra-agency appeals mandated either by statute or by agency rule; it would be inconsistent with the plain language of [§704] for courts to require litigants to exhaust optional appeals as well.” Darby v. Cisneros, 509 U.S. 137, 147 (1993).

The answer to the threshold question whether a RADV overpayment determination constitutes “final agency action” is beyond the scope of this installment. Needless to say, a substantial argument can be made that such an overpayment determination does, in fact, satisfy the Supreme Court’s standard for determining whether agency action is “final” within the meaning of the APA. See Bennett v. Spear, 520 U.S. 154, 177–78 (1997) (“As a general matter, two conditions must be satisfied for agency action to be ‘final’: First, the action must mark the consummation of the agency’s decisionmaking process ... —it must not be of a merely tentative or interlocutory nature. And second, the action must be one by which rights or obligations have been determined, or from which legal consequences will flow ....”) (internal quotation marks and citations omitted).

Moreover, it would appear that a substantial argument can be made that §704’s language regarding reconsideration requests or intra-agency appeals not being necessary applies as well. No statute of which we are aware requires a MA organization to exhaust whatever administrative remedies CMS decides to create on its own accord. Recall also that §704 provides that reconsideration requests or intra-agency appeals are only necessary if the agency “otherwise requires by rule and provides that the [agency] action meanwhile is inoperative ....” It does not appear that CMS has issued such a rule in the RADV context.

Additional Considerations

Solely because one may be able to make a substantial argument that a MA organization does not have to exhaust administrative remedies before challenging a RADV overpayment determination in court does not necessarily mean that a MA organization should forgo exhaustion of administrative remedies. At a minimum, a MA organization can reasonably expect significant motion-to-dismiss practice by CMS in the event the MA organization jumps to court immediately, thereby producing at least some delay similar to that attendant to the administrative appeals process sought to be avoided.

MA organizations faced with the exhaustion question may wish to weigh the following considerations, among others:

- Does the overpayment determination expressly provide that the amount in question will not be offset until the MA organization has been given an opportunity to exhaust its administrative remedies, which is a practice CMS has stated it follows in certain analogous recovery audit contractor settings but has not yet clearly stated applies in the RADV context?

- Does an overpayment determination that is limited to sample enrollees (e.g., a RADV audit report related to payment years 2011 through 2017, according to CMS’s recent final rule) warrant the expenditure of time and resources necessary to justify administrative and/or judicial review if, in fact, the overpayment determination is in a relatively modest amount?

- Does an overpayment determination calculated using contract-wide extrapolation (i.e., a RADV audit report related to payment years 2018 forward) involve issues conducive (in theory) to correction in the administrative appeals process CMS has created, such that a MA organization should give the administrative appeals process an opportunity to correct such errors in an effort to meaningfully reduce the overall overpayment calculation? For example, does it appear that CMS’s overpayment calculation with respect to sample enrollees suffers from plain error, whether it be documentation-related or mathematical?

- Does an overpayment determination calculated using contract-wide extrapolation predominately or exclusively involve legal questions that CMS has indicated cannot be adjudicated in the administrative appeals process (e.g., challenges to methodology such as whether CMS has exceeded its statutory authority in using extrapolation in the MA context), whereby forgoing an administrative appeal—or dually filing such an appeal and court-based litigation—may be worthwhile in an attempt to speed resolution of those legal issues?

MA organizations only have 60 days from the issuance of a RADV audit report in which to initiate an administrative appeal. 42 C.F.R. §422.311(c)(5)(ii). Therefore, it may be prudent for MA organizations subject to RADV audits to begin considering their litigation options now rather than wait for the issuance of an adverse audit report.